15 Seconds of Fame: Why Post-2015 Doesn’t Need More ‘Participation’

The UN’s commitment to participation is commendable, but genuine inclusivity is about more than just poll-taking of the poor and a seat at the table for a lucky few NGOs.

By Lyndsay Stecher

The scramble to replace the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) is well and truly on. The jury may still be out on just how successful the goals – which set various development targets to be met by 2015 – have proven, but with their expiry date just two years away, there is a clear sense that for the post-2015 agenda, something different is needed.

And if the sounds coming out of the UN are anything to go by, that something different is ‘participation’.

One of the major criticisms aimed at the MDGs has been the lack of inclusivity that went into their drafting, and this time around, the UN seems keen to make amends. Official statements and tweets have all emphasised the importance of including those living in poverty in the process of forming the post-2015 goals; a glossy World We Want interactive website whose proclaimed mission is “to amplify people’s voices in the process of building a global agenda for sustainable development” has been launched; and this June, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon vowed, “I want this to be the most inclusive development process the world has ever known”. Furthermore, in a couple days on 17 October, the UN will mark the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty under the theme: “Working together towards a world without discrimination: building on the experience and knowledge of people in extreme poverty”.

However, away from the sound and fury of the new buzzword echoing around UN corridors and development roundtables, questions persist about the actual substance of this commitment to ‘inclusivity’. After all, while the concept is undoubtedly a positive one, if attempts to ensure the participation of the poorest are not deep, meaningful and – crucially – structural, there is a risk that ‘participation’ could be diluted down to a mere slogan and appropriated by those in power to legitimise decisions that are ultimately still their own.

Another day, another “multi-stakeholder panel”

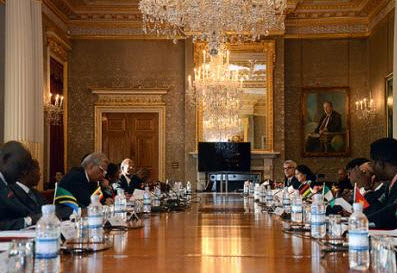

So what does this UN inclusivity look like in practice? Well, the devil is, of course, in the detail, and perhaps the best place to start looking is the nexus of countless consultation meetings, panels and events organised by the UN at which the post-2015 goals are negotiated and discussed. While on the surface these are open to civil society participation, behind the scenes things are a little more complicated. At first glance, even if civil society is represented, it can be easy to lose sight of it amongst the lists of “eminent” speakers. But in fact, just turning up can be a bridge too far for many.

Firstly, for NGOs not already in official “consultative status” with the UN, their presence at meetings has to be approved by all UN member-states; that is to say, specific NGOs are only ‘welcome’ if no-one (and it only takes one state) objects to their attendance. According to Madeleine Sinclair of the International Service for Human Rights, this ‘no-objection’ policy “not only risks excluding relevant and valuable voices, but can also lead to censorship and politically motivated exclusion of critical voices”.

Secondly, even if permission is granted, there remain significant logistical and financial challenges. Places at events are limited, and a scarcity of funding assistance for visa and travel expenses rules out many organisations without the necessary means themselves.

Noah Musoke of the Volunteers for Development Association in Uganda, for example, was approved to attend the special UN General Assembly event on the post-2015 goals on 25 September, but could not afford the expenses and was denied a travel grant. Although the forum was technically open to him, the reality was very different. Without small NGOs’ ability to participate, Musoke worries that the post-2015 framework will feel like “an imposition of the foreign agenda”.

Chinyere Ezenwokike, from the Tomorrow’s Women Development Organisation in Nigeria, also had to pull out due to insufficient finances. “Accessing funds from UN organisations in Nigeria can be very taxing,” she tells Think Africa Press, “especially if one does not have a prior relationship or a person introducing the organisation”. With the competition for limited assistance so high, Ezenwokike has witnessed a strengthening culture of ‘it’s not what you know but who you know’, and expresses her disappointment at her inability to attend the UN event: “This is too bad because it kills the dreams and intentions of the civil society activists”, she says.

15 seconds of fame

For those lucky enough to make it to meetings, the problems and dangers of disappointment don’t end there.

Many events are simply too short for in-depth engagement; the upcoming People’s Voices Series on 17 October, for example, is scheduled to last just 90 minutes and will start with a series of pre-prepared video presentations. And when civil society groups do get the chance to speak, their participation can often seem cursory and token.

Duncan Green, Senior Strategic Advisor for Oxfam, for example, has described a personal “low point” when 200 NGOs involved in a High-Level Panel consultation were each given just 15 seconds to talk; in the end over half didn’t get the chance to speak at all.

Justin Tyoakaa from the Martina Centre for Sustainable Development in Nigeria, who attended the much-hyped 25 September UN meeting and surrounding events, similarly believes that participation can be completely superficial.

“Sitting in these meetings without giving a single contribution removes the sense of participation and creates more of an elitist approach”, he says. “Decisions appear to have been taken and simply brought to meetings for rubber stamping. There’s no voting conducted nor discussions held for or against resolutions.”

Tyoakaa believes that this marginalises civil society and maintains the “undue advantage” of governments in negotiations. “There is no denying the fact that the ‘Major Stake Holders’ – i.e. governments – are rather allowed to dwarf the voices of the ‘Ordinary Stake Holders’ – i.e. civil societies”, he says.

This is something with which Paul Quintos of IBON International, which launched the Campaign for People’s Goals to strengthen grassroots voices, agrees. Quintos argues that the UN has “hardly managed” to reach out to organisations not already involved in advocacy or monitoring, and believes that “many events were organised in haste, trying to beat the UN calendar”. Rather, he says, “public debate should have been promoted in village assemblies and real town hall meetings, allowing ideas to percolate from below.”

I participate? E-participate

However, the UN’s attempts at inclusivity are not restricted to such international events, and the organisation might argue that initiatives such as their World We Want online platform offer exactly that opportunity for ideas to be shared and expressed from ‘below’. Though some admirable national-level consultations have taken place on the ground, the site works mainly through online discussions and aims to “gather the priorities of people from every corner of the world and help build a collective vision”. It seeks to reach out to people far and wide to get their opinions, and does this through such things as its MyWorld survey, which invites users to pick six issues from a list of 16 that they see as the most important.

But as well as being overly simplistic and somewhat condescending, many of these measures – like civil society organisations given 15 seconds to speak – are also highly superficial, and Green dismisses such attempts at participation as “pretty perfunctory ‘clicktivism’”.

Furthermore, these initiatives can suffer from problems of representativeness. According to MyWorld’s own data, two thirds of survey respondents were actually from countries which rank in the middle to the very top of human development indices. And users with post-secondary education comprised the single largest educational demographic. If the perspectives of the poorest are represented in such forms of participation, they are heavily crowded out by those of the privileged.

Talking more broadly about the consultation process, Bernadette Fischler, Policy Analyst on post-MDGs for CAFOD, suggests that the volume of discussions has reached its maximum “dosage”, cheapening individual contributions.

“This sheer number of options to input jeopardises clarity and advance planning, and presents a real risk for inclusivity”, she says. “A multitude of differing consultations poses a real risk of losing or muffling valuable voices since only those NGOs with enough time and resources are able to cover all the bases to get heard”.

Stepping up

The UN’s commitment to reach out to those previously excluded is no doubt commendable, but so far the routes to enhancing participation have largely been insufficient. The good news, however, is that a number of organisations have sprung up to fill the gaps in the UN’s ‘inclusive’ process and have shown that while participation is difficult, it is not impossible.

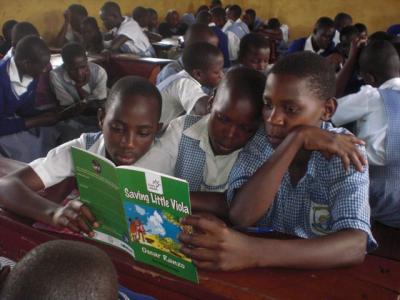

The Participate Initiative, for example, puts cameras and other tools in the hands of the marginalised to tell their own stories, and this summer conducted ground-level panels (GLP) in four countries. At these GLPs, a diverse range of individuals – including those suffering from rural poverty, internally displaced people, members of nomadic indigenous communities, and sexual minorities, amongst many others – were brought together to discuss the challenges confronting them and express their visions for development.

These GLPs have been praised for focusing more on participant challenges than time constraints, with Green contrasting them with “all that superficial online ‘tell us what kind of world you want’ nonsense’”.

However as Joanna Wheeler, co-founder of Participate, explains, the importance of the GLPs goes beyond the discussions themselves. Participation also needs to be about building capacity for the future.

“In order to understand how people have been left behind by the MDG approach, we need to understand what prevents people from making the changes that they are calling for, and how they think these obstacles can be overcome”, she tells Think Africa Press.

Indeed, genuinely enhancing inclusivity is not about a one-off garnering of opinions, but something more long-term and structural.

As Wheeler puts it, “Citizen participation in the new global development framework is not just about a small global elite in the UN ‘hearing the voices of the poor’. Meaningful participation is about creating sustainable and long-term mechanisms for citizens to be involved in decision-making at all levels – from local to global”.

This position is supported by the African Common Position, a group representing 53 African countries, which has criticised the post-2015 development agenda for focusing on outcomes rather than enablers of development.

Ultimately then, inclusivity is about more than just coming up with technically-effective and efficient ways of gathering information in remote areas. It is about more than taking polls of the poor that can be cited in faraway international meetings. It is about more than adding a few extra voices to the growing hubbub clamouring to shape the post-2015 agenda. Genuine participation of the poorest is about politics and power. And the imbalances that have so far stymied meaningful participation are arguably the same ones underpinning the main problems with the UN’s post-2015 High-Level Panel – a failure to address the root causes of poverty; a preoccupation with the market rather than unemployment and deprivation; and a failure to tackle the inequality in wealth, resources and, crucially, power.