In 1987, Blaise Compaoré overthrew Sankara and took over the presidency. 27 years later, Sankara’s ghost may be coming back to return the favour.

By Brian Peterson

30 years ago, on 4 August, 1984, the former French colony of the Upper Volta was re-baptised as ‘Burkina Faso’ amidst a revolutionary process that proved to be one of the most inspiring, yet ultimately tragic, episodes of modern African history.

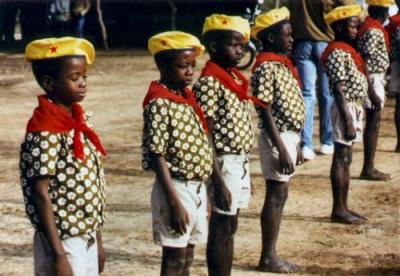

In 1983, the young Captain Thomas Sankara had come to power in a popularly-supported coup d’état and − with broad support from leftist political parties, students, women, and peasants − initiated a range of ambitious projects, including the country’s name-change, that aimed to make the country more self-reliant and free of corruption. Sankara also sought to decentralise and democratise power in order to facilitate more participatory forms of governance, though elections for national offices were never attempted.

By many measures, this visionary project was enjoying a number of promising successes, but on 15 October 1987, Sankara’s experiment and life were cut short when a group of fellow soldiers, led by his former close ally Blaise Compaoré and backed by foreign powers, murdered him. Compaoré promptly took the reins of government effectively ending the revolution.

In the 27 years since Sankara’s overthrow, Compaoré has managed to keep a hold of power and largely ruled with impunity, though there have been periodic protest movements. Most notably, there were widespread demonstrations in 1998 after the journalist Norbert Zongo was killed, while 2011 also saw a marked rise in protests and mutinies.

And now, over the past year, the political opposition has reorganised itself once again and sharpened its message in anticipation of the presidential elections due in November 2015. So far, the most heated dispute has erupted over the issue of term limits. In 2000, the new Article 37 of the constitution reduced presidential terms from 7 to 5 years and imposed a two-term limit. Since then, Compaoré has been re-elected twice meaning that he would not be eligible to run again in 2015, but the ruling party is now calling for a referendum on the article.

It is in this fraught context that the streets of the capital Ouagadougou have become restive today and that the words and images of Thomas Sankara have been revitalised − his quotes declared at demonstrations, his face printed on posters and t-shirts, his revolutionary slogans such as “Homeland or Death, We will Overcome” remembered and recited. With a revived revolutionary spirit, the people have boldly taken up where Sankara left off, bringing to life his assertion in 1987, as rumours of a planned coup began to spread, that “Even if you kill me, thousands more Sankaras will be born.”

Spearheading the wider movement − dubbed ‘That’s Enough’ − has been the Balai Citoyen (“Citizen Broom”) collective and its main leaders, the reggae musician and radio host Sams’k Le Jah and rapper Smockey. The symbol of the broom represents both the neighbourhood cleaning groups that Sankara initiated and the need to clean the country of bad governance and corruption today. The protesters want Compaoré gone, and there’s a prevailing sense that they will not relent until this happens. The movement is peaceful and festive and inspired by the youth movement in Senegal known as Y’en a marre (“We’re fed up”) which played a role in forcing President Abdoulaye Wade from office in 2012.

The fall of Sankara

As many know, the name ‘Burkina Faso’ translates as “Land of Honest People” or “Land of Incorruptible People”, and this moniker seems to capture what it means to be Burkinabé – honest, hard-working, proud and free. The name additionally reflects the multi-ethnic vision and nation-building aspirations of Sankara in that it combined the Mooré word for ‘honest’ (Burkina) with the Jula word for ‘homeland’ (Faso).

But the name change was also a statement against imperialism. Speaking about the issue in Harlem, New York City, on 2 October 1984, Sankara explained: “We wanted to kill off Upper Volta in order to allow Burkina Faso to be reborn. For us, the name of Upper Volta symbolises colonialism.” On another occasion on French television Sankara expanded, saying: “Upper Volta doesn’t mean anything for anyone, particularly for us, the Burkinabés…. By contrast, Burkina Faso is a name drawn from the land itself, that has meaning in our language − the ‘Country of Honest Men.’”

In essence, the name change was about decolonising minds and freeing Burkina Faso from foreign cultural and economic domination, and many Burkinabés who lived through these revolutionary years remember feeling a new sense of pride in being from Burkina Faso and in having the dynamic and bold Thomas Sankara as their president. Outside the country, Sankara also became something of a revolutionary hero, being labelled the “African Che”, particularly among the youth. His famous adage, “Everything that man can imagine, he is capable of creating,” injected optimism and hope into many people’s lives.

True to the country’s new name, Sankara would live up to the highest standards of incorruptibility. At a time when most African heads-of-state used power to enrich themselves, Sankara set out to end the practice of employing political power for personal gain and lived a life of frugality and simplicity, dying with few possessions and scant money or real estate. Sankara also sought to end decades of French colonial and neo-colonial domination by reaching out to countries in the non-aligned world. His revolution restored the dignity of the people by giving them a political voice and through social and agrarian reforms. He addressed a wide array of problems with relentless vigour, ranging from environmental degradation, women’s rights, education, local cotton textile production, and public health. And while there were errors along the way, as Sankara frequently admitted himself, he persistently sought to correct them.

Following Sankara’s assassination, however, Compaoré did his best to turn all this on its head. He was quick to blame Sankara’s policies for all the country’s problems, promised to “rectify” the revolution, and used the media to defame him. And for decades now, Compaoré and his ruling party, the Congress for Democracy and Progress (CDP), has managed to keep the opposition at bay. This is partly due to Compaoré’s use of clientelist networks, though the fragmented nature of the opposition and wide proliferation of political parties have also enabled the CDP to dominate.

Meanwhile, the “Sankarist” parties have long lost their revolutionary edge. The most prominent leader among these groups, Bénéwendé Sankara (unrelated to Thomas), came second in the 2005 presidential election (albeit with less than 5% of the vote), but he has since seen his political fortunes wane. Furthermore, the social movement currently brewing in Burkina Faso has sought to distance itself from the old Sankarist parties anyhow as they view them as having tarnished Sankara’s image with their political opportunism.

Shifting sands?

Although the relations of force within Burkina Faso have been firmly in Compaoré’s favour since 1987, this may now be shifting on various fronts. Most notably, at the start of January 2014, 75 key political figures from Compaoré’s party resigned. A couple of weeks later, following a mass protest against the proposed referendum on Article 37, these former officials formed the People’s Movement for Progress (MPP).

This new opposition party is led by some of Compaoré’s closest former allies − including Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, Salif Diallo and Simon Compaoré (no relation of Blaise) − all of whom are skilled political operators. Kaboré, for instance, was president of the National Assembly from 2002 to 2012 and had been president of the ruling CDP before his defection. The MPP’s opposition to attempts to change Article 37 may well be self-serving, but it allies them with a social movement that places democratic, transparent governance and respect for the rule of law firmly centre stage.

Compaoré responded quickly to these events by establishing the Republican Front, a loose coalition of mostly pro-CDP parties that has been taking the argument to the people that it’s better to hold a referendum on Article 37 than hurl the country into chaos.

This year then, demonstrations and counter-demonstrations have been held as both the opposition and the Republican Front tour the country. In the likes of Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso’s second city, opposition parties have come together to form local Committees Against the Referendum (CCR) coordinating their tactics with leaders in Ouagadougou. Meanwhile Compaoré has taken his Republican Front on the road, organising mass rallies in the capital and, in a bid to impede his opponents as much as possible, has gone so far as to cancel the passports of MPP leaders.

A thousand Sankaras

Compaoré may well have several tricks up his sleeve, but one of his problems in all this is that the ghost of Thomas Sankara never disappeared. Despite Compaoré’s efforts, his predecessor’s ideas and inspiration would not be easily erased from history, and for many Burkinabés, it was the unceremonious manner in which their beloved leader was thrown into an unmarked grave and the dragging of his name through the dirt afterwards that stings the most. Fighting for the truth around his death is a question of dignity and respect for the man they see as having given his life for their country. For years, the issue was debated primarily within the context of the “Justice for Sankara” movement in France and on active social media networks, but it is now spilling out into the streets with renewed force.

In 2013, after years of pressure from opposition members, a French member of parliament called on the French government to open its archives and investigate Sankara’s death. In April 2014, however, the court in Ouagadougou ruled, after years of delay, that it would not allow DNA experts to access Sankara’s tomb in order to verify the identity of his body. In recent weeks, during an interview, Compaoré did finally confirm that “Thomas is buried in the Dagnoën cemetery in Ouaga,” but nothing more was revealed.

In the meantime, the ‘little Sankaras’ have come of age. As rapper Smockey said, quoting Sankara: “A mobilised and determined youth is not afraid of anything, even an atomic bomb.” And after years of fear and silence around his death, the time is ripe for the youth to pick up his legacy. Young Burkinabés listen to Sankara’s speeches on cassettes, watch videos about him on the internet, and are using this history as a weapon in their struggle today. Despite state efforts to suppress Sankara’s memory over the past three decades, the people have rediscovered the revolutionary patron saint who brought pride and dignity to Burkina Faso. This symbolic figure might be precisely what Burkinabés need to face the political challenges ahead, knowing full-well, as Sankara stated at the UN General Assembly in October of 1984, that, ultimately, “Freedom can only be won through struggle.”