What motivated Mali’s unlikely mutineers and what lies in store for Mali’s political system?

By James Schneider

Rebellious Malian soldiers declared today they had taken power, removing President Amadou Toumani Touré. The coup is led by junior officers disgruntled by the government’s failure to put down a rebellion by Tuareg separatists in the north of the country.

The coup leaders have formed the National Committee for the Return of Democracy and the Restoration of the State (CNRDR), declaring the constitution suspended.

“The CNRDR … has decided to assume its responsibilities by putting an end to the incompetent regime of Amadou Toumani Touré,” said Lieutenant Amadou Konare, spokesman for the CNRDR, in a televised address.

“We promise to hand power back to a democratically elected president as soon as the country is reunified and its integrity is no longer threatened.”

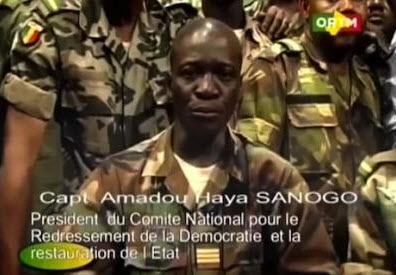

CNRDR appears to have around two dozen members, all in their twenties and thirties. They are led by Captain Amadou Sanogo, who according to the RFI was an English teacher at the Kati barracks, 13 km from the capital Bamako, where the coup commenced.

From mutiny to coup

The mutiny at the Kati barracks began yesterday following a visit by Defence Minister General Sadio Gassama. It appears that the minister failed to address the troops’ grievances over the government’s handling of the Tuareg rebellion in the north. Soldiers fired shots into the air and stoned the minister’s car. Following this insurrection, the troops captured the state television station, first taking it off air, then playing music videos. President Touré used Twitter to insist this was a mutiny and not a coup. Shortly after his statement, soldiers surrounded the presidential palace. When they broke in and reportedly looted the palace, Touré had already escaped. The presidential twitter account has not been used since yesterday evening. AP now report that Touré is in a Bamako military barracks protected by his elite guards, the Red Berets. France has called for his “physical integrity” to be respected.

The rebellion next spread to Gao, a city in the north of the country which serves as the military base point for operations against the Tuareg separatists. It is reported that senior officers were arrested by their juniors in support of the CNRDR and against the government and military high command’s handling of the northern conflict. On Tuesday, Jeune Afrique reported that recent defeats coupled with claims of corruption had created “a climate of distrust of the Malian army’s top brass” by troops.

It has been reported that Gassama is being held by troops loyal to the CNRDR, along with the former foreign minister and three current ministers. The South African government has called for “senior military officers and political leaders being held hostage” to be released.

Relatively peaceful

Although events have been dramatic they have remained relatively peaceful. 20 people have been admitted to hospital, mostly from injuries sustained from stray bullets fired in the air in support of the coup. There are no reported fatalities.

Flights have been cancelled. The CNRDR has instituted a partially observed curfew and have issued an order to seal the country’s borders. Banks, government buildings, petrol stations, and many shops are closed.

It is likely that the coup leaders will have significant, although not total, support on Bamako streets. Last month saw angry protests, which also started in Kati, against the government’s perceived poor handling of the Tuareg rebellion. Tyres were burned in the street and the presidential palace was surrounded by protesters. The CNRDR appears to be channelling some of that anger. Indeed, in parts of Bamako “people are celebrating with the soldiers”, according to an eye witness source in conversation with the BBC’s Nick Ericsson.

Who are the CNRDR?

Very little is known about the CNRDR. They have released televised statements, both showing around two dozen relatively young men from different sections of the military, and one policeman, in military fatigues. Captain Sanogo appears to be the highest ranking among them.

The revolt, at least for now, does not appear to be orchestrated by senior political figures. Rather, the actions of the coup leaders’ suggest opposition to both civilian and military high command. Not only have ministers and senior military figures been arrested but candidates for next month’s presidential elections, for which Touré expected to have ran, have been targeted. Soumaila Cissé, one of the four frontrunners for those polls, had his house broken into and looted in the early hours of this morning.

Whilst the CNRDR frames itself as wanting to return the country to democracy swiftly, as Touré did after his coup in 1991, their interests appear more military than political. Their grievances predominantly stemmed from the campaign in the north and their only hint at future actions relates to the war. In Konare’s statement, the CNRDR promised to return the country to elected civilian rule “as soon as the country is reunified and its integrity is no longer threatened”. In short: we’ll give back democracy once we’ve won the war.

It is also possible that Sanogo, Konare and the CNRDR are accidental coup leaders. Early reporting by Africable TV, which claimed to have spoken to some of the mutineers, suggested that the rebellious soldiers were demanding more resources for the war, not attempting to remove the government. Indeed, apart from rushing to take state television off air, their actions do not seem planned. They did not have a prepared communique to announce, their television broadcasts suffered from sound problems and appeared amateur. This may simply be a protest, that became a mutiny, and evolved into a coup.

What next?

Whether planned, professional or not, the CNRDR coup could easily hold. If they can keep looting by low ranking soldiers, which is increasing being reported, at bay, they should be able to rely on the support of Bamako’s populace. And if they can provide sufficient weaponry and pay for the battle with the Tuareg rebels, then they should guarantee, at least for now, the support of rank and file troops.

Touré or any possible allies in military high command may prove unable or unwilling to stage a fight back. Although it appears that Touré elite troops, the 33rd Parachute Regiment, remain loyal, many are currently deployed in the north. He only had three months left in office and if his safety and assets can be secured, he may not respond with violence.

It remains to be seen whether senior officers will accept the intrusion of their juniors into public life, although judging from events so far, military high command is not popular in the Malian armed forces. Civilian political leaders and their parties may quietly wait out the predicted six to twelve month delay in the polls.

Although the coup has received complete international opprobrium, with everyone from ECOWAS to the UN condemning the CNRDR, it is highly unlikely that the international community can do much about it. Following the pattern of recent coups in the region, international actors criticise, withdraw funding from and exclude coup-formed governments, but do not intervene further. Evacuating Moses Wetangula, Kenya’s foreign minister, who is stranded in Bamako, is the international community’s only likely success.

The CNRDR came into existence due to the war in the north. This war is set to intensify. In order to maintain control, the coup leaders must have some sort of quick and visible military success, such as recapturing rebel-held towns. The Tuareg rebels are set to take advantage of the confusion caused by the coup and escalate their attacks.

Government workers return to the office next Tuesday, with a food crisis, a refugee crisis and a war in the north to address. If the CNRDR manages to consolidate its grip on power, it will have its work cut out.