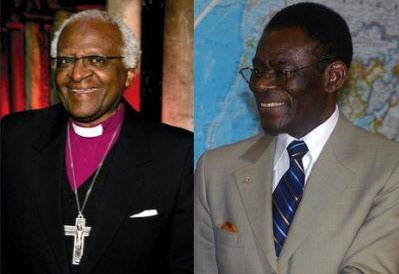

Archbishop Desmond Tutu argues that the people of Equatorial Guinea need justice, not a $3 million science prize funded by their president.

By Desmond Tutu

Over the past year, the world has watched with great interest as the Arab Spring has dissolved decades of repression. Citizens weary of injustice have stood up and demanded control of their destinies. I wish that oppressed people everywhere in Africa could benefit from the dramatic changes we are witnessing in North Africa.

The people of Equatorial Guinea, for instance, an oil-rich country home to the continent’s longest-ruling leader, Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, have endured decades of repression, and many remain mired in poverty despite the country’s considerable natural resource wealth. Torture, extrajudicial killings, arbitrary detentions, and harassment of journalists and civil society groups have been well documented by the United Nations and other sources.

Credible allegations of high-level corruption —including by President Obiang and his eldest son— are the subject of judiciary investigations around the world. Meanwhile, spending on education is very low, even compared with other African nations that are less blessed with natural resources than Equatorial Guinea.

In February, President Obiang’s government imposed a news blackout on the political protests in North Africa, and later denied its own citizens the right to hold peaceful demonstrations.

Despite this abysmal record, in 2008 UNESCO agreed to establish a science prize named for and funded by President Obiang aimed at “improving the quality of human life.” UNESCO suspended the prize in October 2010 after an overwhelming number of Equatoguineans, human rights groups, press freedom organizations, anti-corruption groups, public health professionals, prominent writers, and esteemed scientists from Africa and around the world voiced their outrage over the prize.

I myself, in solidarity with the people of Equatorial Guinea, joined in this effort. In a letter addressed to UNESCO in June 2010, I expressed my concern over the prize and noted that the UNESCO-Obiang prize’s $3 million endowment should be used to benefit the people of Equatorial Guinea —from whom these funds have been taken— rather than to glorify their president.

Now, less than one year later, as the 187th session of UNESCO’s executive board gets under way, the organization is considering revisiting its October 2010 decision to suspend the prize indefinitely. Earlier this month, a proposal to reinstate the prize was put forward in the name of the African Union, which President Obiang currently chairs. That request has been included on the UNESCO board’s meeting agenda and could be considered as early as September 29.

In numerous speeches to international audiences, including many in his role as the rotating AU chair, President Obiang has stated his commitment to democracy, human rights, and good governance. His words, however, ring hollow since they are often not applied inside his own country.

In his address this past week at the United Nations General Assembly, President Obiang advocated that democracy “must evolve in harmony” with a country’s local culture. Unfortunately, the citizens of Equatorial Guinea have never had a free and fair election through which they could choose their own destiny or shape a democracy according to their values.

While I welcome President Obiang’s decision to release 22 political prisoners in June 2011 during a ceremony to commemorate his birthday, we must remember that his country’s judiciary lacks independence and the rule of law is very weak and often violated. Just last year, the government of Equatorial Guinea executed four of its own citizens after kidnapping them from Benin, secretly holding them in detention without access to lawyers or their families, and denying them the right to appeal the court’s decision or even to contact family members before their deaths, which occurred less than one hour after the summary military trial concluded.

After his June 2010 speech at the Global Forum in Cape Town, South Africa, where President Obiang stated his commitment to a five-point program of transparency and political, legal, and economic reform, I encouraged him to follow through on his promises and offered to help in whatever way that I could.

Unfortunately, I find myself instead voicing continued objections to the UNESCO-Obiang prize.

It is unfortunate that the time and resources expended by President Obiang to establish the prize are not directed at implementing the reforms that he regularly mentions. President Obiang should focus his efforts on remaking Equatorial Guinea into an open, rights-respecting democracy fitting for these times.