France needs Niger’s uranium, while Niger needs French assistance. But the relationship is and always has been unequal.

By Sam Piranty.

Last December, as negotiations dragged on between the Nigerien government and the French state-owned mining company Areva over royalties, the latter suddenly stopped production. At the time, Niger had been demanding a better deal for its uranium for over a year and Areva’s decade-long mining contract was about to expire at the end of the month.

As its mining activities came to halt, Areva claimed it had suspended production for maintenance, but many saw it as a political move aimed at putting pressure on the Nigerien negotiators. After all, Niger’s economy is heavily dependent on its huge uranium reserves and its population is already one of the world’s poorest. Turning off that tap could have huge repercussions.

However, in a sense, it is that very discrepancy − between the country’s vast mineral wealth on the one hand, and widespread poverty on the other − that the government was in negotiations to re-assess. According to the International Monetary Fund, Areva’s global revenues of nearly $13 billion in 2013 make the French firm almost twice as big as Niger’s whole economy, and as Areva’s revenues have risen − partly off Niger’s uranium − Nigeriens have remained poor.

In the end, Areva restarted production at the start of this month, but the talks are still ongoing. Niger is reportedly demanding that the royalties Areva’s mines pay increase from 5.5% to 12%, bringing them closer to the 13% Areva pays in Canada and the 18.5% paid in Kazakhstan. However the French-owned company, which has posted losses in recent years, insists that such a change would not make their operations worthwhile.

The result of the deadlocked talks could prove highly significant for Niger, but this is not the first time the West African nation has found itself in this position. In fact, the current negotiations are merely the latest chapter in a long history of France-Niger relations, and unfortunately for Niger, a look back at previous chapters of the story doesn’t offer too much hope for a positive outcome in the one being played out today.

Forming Françafrique

Franco-African relations first began in the late-14th or early-15th century with trade with the coastal regions of what are now Gambia and Senegal. But it was only in the early 17th century that France “began granting trading charters in specified areas as part of an attempt to extend France’s power and wealth,” in the words of political scientist Victor Le Vine. Like most of the European powers, the French initially didn’t venture far inland as trading slaves and resources didn’t require more than a port and a few merchants. However, as the nature of trade shifted so did the means by which to plunder the continent, and by the 19th century, France, along with the rest of Europe’s colonial powers, was moving inland, starting in Senegal.

After its 1871 defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, colonialism was seen as a way of regenerating nationalist sentiment and elevating France’s global status, and with enhanced efforts, by 1900 France had become the second largest colonial power in the world.

This status was officially lost after decolonisation in the 1960s, but in many ways, the end of empire wasn’t quite the rupture it may have seemed. By 1965, despite the formal recognition of independence, many heads-of-state in Francophone Africa had been members of the French parliament and often these elites were part of a French push for cultural dominance, they were what the French called Évolués. Under colonialism, France hadn’t just sought to dominate states but also indoctrinate their citizens. Furthermore, despite a shift in the geopolitical climate, France was in no mood to loosen its grip on its former colonies for three reasons, as explained by political scientist Xavier Renou: 1) France wanted to retain its international status; 2) it wanted to secure access to strategic resources; and 3) it could make huge profits from its system of economic monopoly.

Masterminded by government advisor Jacques Foccart (aka Monsieur Afrique) and initially by President Charles de Gaulle, what resulted was a symbiotic relationship between France’s leaders and those of the its former colonies. Francophone Africa relied on French contributions for sustenance, while France counted on the continent for resources. The former Gabonese president, Omar Bongo, is famously reported to have said “Gabon without France is like a car with no driver. France without Gabon is like a car with no fuel.”

The Franco-African pacte colonial made sure that African financial decisions were made with French interests at heart and that post-colonial Francophone markets were reserved for French companies and traders. And of all the resources available to France, uranium was of arguably the greatest importance − it not only offered economic value, but political and military value, and reified France’s status as a global force . At the end of World War II, France had been left devastated, but the progress of French nuclear scientists in the years following in their first experimental nuclear reactor, Zoé, provided a sense of optimism. As uranium expert Gabrielle Hecht wrote, “nuclear nationalism comforted state leaders anxious about their country status. The French compared reactors to the Arc de Triomphe and the cathedral of Notre Dame.” In a post-WW2 world, global status was increasingly determined not by the size of one’s empire, but the size of one’s nuclear arsenal. France did not want to be left behind, and with special access to Niger and Gabon’s uranium deposits, it would not be.

Having already entered into the pacte colonial, France had a monopoly over the uranium offered in the two countries through French-owned company Cogema (now Areva). This facilitated the energy independence that de Gaulle and France craved, and in return, Niger and Gabon were granted military security, developmental aid and guaranteed markets for their products. Furthermore, as Hecht points out, “France would help defend the new leaders not only against external threats but also against coups d’etat.”

The Nigerien negotiations

Uranium was first discovered in Niger in the northern town of Arlit in 1957 by the French geological survey, and negotiations between France and Niger started in earnest when the former African colony gained independence in 1960.

Niger’s first president, Hamani Diori, faced a difficult balancing act between pleasing the likes of de Gaulle and Foccart in Paris on the one hand, and the newly-liberated Nigerien population on the other. However, France had an advantage in this conundrum – its relationships with former colonies were built on clientelistic networks. They were held together by key personalities and moreover, patrimonialism was rife within the Nigerien state itself, with Diori and his party at the heart of it trying to maintain their dominance. As Bruno Charbonneau explains, French policy in Africa was “more than anything else the result of transnational elites whose main objective is to maintain and to reproduce the social conditions that privilege them.”

Like many other leaders in Francophone Africa, Diori met frequently with Foccart. Foccart was known to be the kingmaker in France’s former colonies and had the means and influence to keep Diori in power when times were tough, but Diori was himself a skilled negotiator. When Diori saw France’s initial plans for the distribution of profits from the uranium mines and was unimpressed, he went straight to Foccart. The French advisor relented and talked to de Gaulle who, according to Hecht, “personally granted a larger percentage of the profits to Niger, throwing in a special development aid package and a promise to send French troops as needed to defend the deposits against Algerian incursions.”

At first, Diori accepted the improved deal, but after a visit to the US in 1960, the Nigerien president realised that uranium was more than just another resource and that he could drive a even harder bargain. He set about pushing for further concessions from France and a significant stake in the mining companies Somaïr and Cominak. He also requested the establishment of a new special investment fund. France conceded to some extent, but Diori’s pressure for a better deal continued through the years, partly driven by the fact that by the early-70s Niger had still not received any dividends from its uranium.

In 1973, Diori gained a new bargaining chip as the global oil crisis pushed France to expand its nuclear power capacity. Diori saw this as an opportunity to strike and, alongside Gabon’s President Bongo, called for a meeting to renegotiate uranium prices. The talks were initially unsuccessful and put on hold.

One week after the meeting, however, de Gaulle’s successor, Georges Pompidou died. And on his way to the memorial service, the relentless Diori tried to arrange a meeting with the prime minister to resume negotiations. This tactless move seems to have been the moment that tipped the balance for France. Diori had pushed too hard. The Nigerien president had been a useful ally, but on 15 April 1974, France decided not to intervene as Diori was ousted in a coup d’etat led by Lieutenant Colonel Seyni Kountché.

There were of course other factors leading to the coup such as the dire economic state of the country and the unrest amongst the military, but France’s inaction was perhaps the most tragic for Diori. After decades of colonial rule and with Foccart’s extensive intelligence networks on the continent, France surely knew what was coming for the president. It’s unlikely the Nigerien and French militaries would not have been aware of each other’s intentions and, moreover, the French still had large numbers of troops in Niger and in neighbouring states. France deliberately looked the other way as Koutché planned his move, and essentially, Foccart had decided to fire Diori.

Back to the future

Fast-forwarding to the current day, the structures and means of coercion in France’s relations with Niger continue, albeit altered through generational changes in personnel, new economic realities, and a shift from a Cold War to a War on Terror geopolitical discourse. Both President François Hollande and his predecessor Nicolas Sarkozy have made lofty statements about ending La Françafrique in recent years, but France’s military presence and continuing economic hold in its former colonies suggest an ongoing and unequal relationship.

In terms of a generational change, the death in the 1990s of leading Franco-African figures such as President Félix Houphouët-Boigny of the Ivory Coast, French President François Mitterrand, and Foccart caused a symbolic rupture in France’s ‘special’ ties with Africa − la Françafrique had always been held together with highly personal relationships. However, to suggest that this shift diminished or ruptured the clientelist structures between France and Africa would be wrong.

Sarkozy certainly didn’t cut the old colonial ties and is even believed to have presided over the marriage of Ivorian president Alassane Ouattara and his wife Dominique in 1990. These weren’t just patrimonial ties, but ‘family’ ties. Furthermore, the extent to which France’s clientelist networks still exist was arguably demonstrated clearly in 2008 when Jean-Marie Bockel, France’s secretary of state for cooperation and Francophonie, was removed from his position just two months after he had criticised corrupt African leaders and urged France to stop giving aid to states such as Gabon. According to Director of Research at the International Crisis Group, Richard Moncrieff, President Bongo had seen the speech and “quickly activated his remarkable network of influence within the French Gaulist movement.”

In terms of economics, the region also remains highly important for France, as a recent Chatham House report explained, pointing out that French companies are “particularly strong in sectors such as logistics, port and rail operations, telecoms, shipping, banking and air transport; they also have significant interests in tropical commodities and agriculture.”

Finally, although the Cold War has subsided, the War on Terror has added a new dimension to the France-Africa relationship. Over the years, there has been growing attention and concern about the Sahel, a region in which al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and other Islamist militant organisations reside, and the US has looked to increase its military presence across the continent, including in Niger, to monitor ‘terrorist’ threats. Recent announcements from Paris suggest that France too is reorganising and perhaps expanding its military capabilities in Africa. France is believed to be setting up extra bases in northern Niger, Mali and Chad, and in a post-9/11 world, Islamist militancy offers France a reason to sit at the top table.

What’s yours is mine

When it comes to France’s relationship with Africa then, it seems the adage that plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose rings true − including when it comes to its ongoing negotiations over Nigerien uranium prices.

France currently sources over 75% of its electricity from nuclear energy and is dependent on Niger for much of its immediate and future uranium supply. This dependence could grow even further when production at the recently-discovered Imouraren uranium deposit is up and running in 2015. The mine is set to produce 5,000 tonnes of uranium per year and would help make Niger the second-largest uranium producer in the world. Areva, which is 87% owned by the French state and holds a majority share in three out of the four uranium mining companies operating in Niger, is funding the new mine.

However, despite Niger’s vast uranium reserves − over which France has an effective monopoly − the country has remained poor. In February 2013, President Mahamadou Issoufou, a former Areva employee, claimed that Niger’s uranium deals generate just 100 million Euros ($140 million) a year, representing just 5% of Niger’s budget. “That’s why I have asked to re-equilibriate the terms of the deal between Areva and Niger,” he said. Issoufou also said Niger has started looking to other countries, saying that his “objective is to diversify our uranium mining partners.”

One can perhaps substitute ‘other countries’ for China, which already owns a 37% stake in Niger’s SOMINA mine and has carried out uranium exploration throughout the country. However, Areva − France by proxy − still holds all the cards given its controlling stakes in the country’s three other mines. Comparatively, Francophone Africa does not receive the same level of Chinese investment as many Anglophone parts of the continent and Niger is no different. French saturation of Nigerien markets leaves little space for other investors, and its grip on the uranium industry is such that hopes of real diversification of investment and competition are slim. And without other prominent competitors, Niger’s position in negotiations with Areva is severely weakened.

Areva’s power in Niger is also exemplified by recent court battles over the safety of the mines. In 2009, Serge Venel, a French miner who worked for Areva in Niger from 1978 to 1985 died of lung cancer. He had previously raised concerns about the lack of health precautions in mines and after his death, doctors said that his unprotected work in the nuclear industry had been the cause of his illness. The French courts agreed, and in 2012 demanded Areva pay Venel’s family €200,000 ($270,000). However, in 2013, Areva won an appeal. The company argued that the COMINAK mine was to blame, not Areva, despite being the majority shareholder in the mine. Proving where culpability lies in mining-related illnesses is particularly tricky, especially when Areva owns all the local hospitals in the area. Serge Venel was able to be diagnosed properly at home in France; Nigerien miners and their families are treated at Areva-owned medical facilities.

Recently, an Al Jazeera documentary and investigation by Greenpeace has further raised concerns about the health effects around the mines in Arlit. Greenpeace claims that radiation around the mines is 100 times the World Health Organsation’s safety levels, while the NGO along with important and extremely active local civil society groups maintain that water used in the towns surrounding the mines has been contaminated, mine vents pump radioactive radon into the air, and tonnes of nuclear waste has been left around the area. The Al Jazeera documentary even showed Areva-employed doctors saying that radiation had been responsible for a local’s death. How Areva responds and whether it will be held accountable, however, remains to be seen.

Ultimately, many of the dynamics at play in the 60s and 70s are still prominent today as a Nigerien president pushes for a better deal of uranium prices once again, France continues to dominate the country’s mining industry, the region remains somewhat unstable, and the French military maintains its heavy presence.

France needs Niger’s uranium, while Niger needs French assistance, both military and economic. But the relationship is and always has been unequal. Despite the both parties need for each other, France has more power to set the terms for this exchange. The current negotiations − coming after years of exploitation by both French and Nigerien elites − may slightly increase Niger’s income from its vast resources, but if history and the current balance of power tell us anything, it’s that the Nigerien people will continue to miss out on the revenues they deserve.

Amendment [20/02/14]: In the original, the ‘pacte colonial’ was wrongly spelt ‘pact coloniale’ and Serge Venel’s surname was mistakenly spelt ‘Venal’. These have now been corrected.

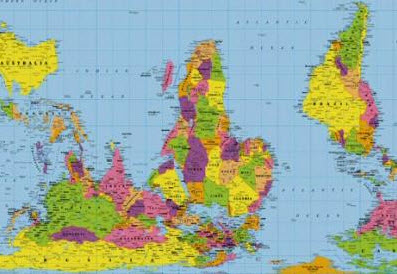

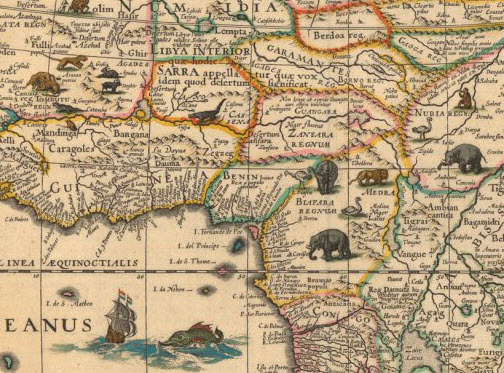

From Willem Janszoon Blaeu’s 17th Century map of Africa.

From Willem Janszoon Blaeu’s 17th Century map of Africa.